February is a short month, only twenty-eight days, and I read twenty-eight books because I was at home the whole time and barely went out—not so much because of the pandemic, though it is not yet over here, but because of disability issues. I did see some local friends, and this last weekend some friends came to visit from Ottawa which was great. But on the whole February was a month with a lot of pain and a lot of days when reading was all I can do. But that’s OK, because there are some wonderful books in the world and I managed to find some of them, and now I can recommend the gems and warn you off the duds.

The Bird of Time, George Alec Effinger (1986)

When Effinger was good he was very, very good, but he wrote some odd potboilers and this was one of them. I had high hopes for this time-travel romp, but there’s nothing quite as disappointing as comedy that falls flat. It didn’t quite make sense, it wasn’t funny, I didn’t care about it at all, and I only finished it because of the sunk cost fallacy. Very disappointing. Go re-read When Gravity Fails instead.

One Summer in Rome, Samantha Tonge (2018)

Romance novel set in Italy. Some implausibilities—a restaurant set where she says it is wouldn’t care about reviews and lists, they’d get enough tourists to do well even if the food was terrible. But what’s really wrong with this is that it’s trying a little bit too hard on the character stuff; the heroine doesn’t believe she deserves love because she’s an orphan and the hero is blind, and that could have been good but it’s all a little bit too obvious and laboured. However, while not exactly good, this is a book with its heart in the right place.

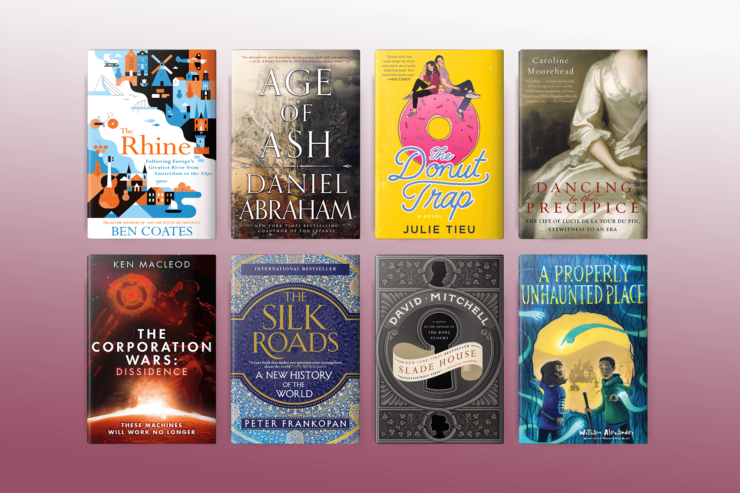

Slade House, David Mitchell (2019)

I seem to have decided the order I’m reading Mitchell is the order Amazon are selling them cheap for the Kindle, which may be a mistake. This book was brilliant but it was also horror, and way too scary for me. I don’t want to read things that are this dark, no matter how well they’re written; indeed, when it comes to being frightening well written isn’t a plus. There are two… kind of vampires, and a truly terrifying haunted house, and lots of really great well-drawn characters who have terrible things happen to them. It makes it clear that some things that are edge-of-genre, maybe real and maybe not real in the other Mitchell I have read were, in fact, real and connect to some of this in ways that may become clear in later books, maybe. Mitchell is a wonderful writer, and if you’re not put off by the fact that this is very scary and dark you should absolutely read this book. But maybe I shouldn’t have.

Finding Audrey, Sophie Kinsella (2015)

A YA book about a teen with anxiety finding a way to be in the world. Sweet and funny, with a very good, if not necessarily plausible, love interest, and great younger brother. I prefer her books about older women because lots of people are writing about teens growing up and few are writing about people in their twenties growing up, but this was fun.

All You Who Sleep Tonight, Vikram Seth (2021)

Brilliant poetry collection from the amazing Vikram Seth. His grip on scansion is inimitable, and he writes about such important things. I just want to quote half the book, but have the short beautiful title poem:

All you who sleep tonight

Far from the ones you love

No hand to left or right

And emptiness above.

Know that you aren’t alone

The whole world shares your tears

Some for two nights, or one,

And some for years and years.

Just read this book if you like poetry at all, it’s doing everything poetry does… it’s beautiful and profound and timely.

A Properly Unhaunted Place, William Alexander (2017)

Bath book. This is a new low, reading a signed book in the bath. But… I never drop things in the bath, and I am increasingly not reading paper books anywhere except in the bath. I didn’t drop it, and it was great. This is a middle grade book about a world where ghosts are real and present and you can’t get away from them and have to find ways to live with them, except in this one town, which has no ghosts—until the book happens.

It’s about a Ren Faire and a library, it’s about mixed race kid heroes, one boy and one girl, and what it’s really about is how you can’t get away from history and pretend it didn’t happen. It’s great. It would make a perfect gift for any eight- to ten-year-old who reads, and you’d probably enjoy reading it yourself before you passed it on. I would say I wished Will Alexander would write more stuff for grownups, but in fact maybe kids need him more.

Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino (1972)

Sort of re-read. When I was in Venice in August the friend I was travelling with was reading this, and whenever we sat down to rest on a bench or in a cafe he would read me one of Calvino’s brief strange descriptions of cities. I’d read the book years ago in Italian when I didn’t actually speak Italian but my Latin was great, and it makes a lot more sense in English… but not as much more as I’d imagined it might.

The conceit of this short book is that Marco Polo is talking to the Great Khan and describing fifty cities, all of which are in some way Venice. The descriptions are both lyrical and thought provoking, and some of them are wonderful. There’s an irritating thread of sexism running through the book—women are always the mysterious other in these cities, very much in the male gaze. However, it’s gorgeous. The ideal way to read it is to have someone read it to you in pieces in different locations in Venice, but failing that read it slowly one city at a time, don’t try to read it as a novel.

The River South, Marta Randall (2019)

Sequel to Mapping Winter which I read last month, and even better. This is a coming of age story in the best way, someone growing up and discovering who they want to be and who they can be. It’s fantasy without magic set in the history of another world, which I think I might start calling “otherhistorical fantasy” for lack of a better term. Great world, nice to see more of it, excellent story, very real characters. I especially enjoyed the travelogue aspect to it, and the way it all linked up to the previous book at the end when it hadn’t shown much sign of it until then. Very satisfying reading experience. Must read more Randall.

Expiation, Elizabeth von Arnim (1929)

Wonderful sly book about a woman whose husband dies and leaves her nothing because he secretly knew that she was secretly having an affair—but it’s not that kind of book at all, not the way a modern book would be. It’s really about being stifled by respectability and the way it was so difficult for women to lead their own lives when economic independence was so difficult. This is very funny in parts and appalling in other parts, and the absolute best bit is the reunion of two sisters. Nobody writes like von Arnim, and nobody wrote like her even when she was writing, and I’m so glad I stumbled across her. She has a very acute observation and wit, and she’s writing about a level of society people don’t often notice. Also, she’s a first-wave feminist but she never seems to get talked about as one.

This is the first of the books I read in February where I thought how differently it would have been written if it were written now, as a historical novel. I don’t think it would be the same in any feature—you wouldn’t have a failing hotel in Switzerland and poverty, you wouldn’t have Milly’s brothers-in-law finding her middle-aged plumpness more attractive than their wives’ slimness, and you just wouldn’t have this stratum of society where respectability is everything. Nor would you have an adulterous romantic relationship that had burned out all the romance and lust and was worn down to a nostalgic routine.

The Diddakoi, Rumer Godden (1968)

Re-read, bath book. When I read L.M. Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe aloud over Christmas I was surprised and horrified to discover the anti-Roma Suck Fairy had been at it. And that made me think of this book, also a children’s book that I read as a child, which is directly about prejudice and difficulty experienced by a half-Roma child. As the title indicates, this book uses words as they were used in 1968, where the external polite term was travellers, the internal term was Romany. Other words, negative both now and then, appear in the text mostly in the context of being used as slurs, but sometimes not.

This is an interesting but not always comfortable book to revisit. Godden was sympathetic and had clearly done her research, and meant well. And I read this as a child and for me it was a corrective to all the books with gypsy curses and gypsy thieves. It was neat to see that there’s what reads clearly to me now as a gay couple—it was 1968, only a year after homosexuality was decriminalised in the UK, and this was a children’s book, but as much as you could have a visible gay couple I think Godden does here.

But there are jagged edges and some problematic and insufficiently examined issues. What’s brilliant is the child’s point of view, indeed the switching points of view. Godden is always good at that. And she pulls no punches on the prejudices and what Kizzy goes through in school. She deserves credit for writing about this, like this, as early as this. I don’t know that I’d give it to a child now—even though it fulfilled its purpose in making child-me less prejudiced. It’s also, like all Godden, enjoyable to read, aside from everything else.

The Day We Meet Again, Miranda Dickinson (2019)

Romance novel in which two people meet in St Pancras Station and fall in love while waiting for delayed trains, but they’re headed in different directions for a year, and agree to meet up when the year is over. The part when they are travelling and communicating long-distance was pretty good, though it wouldn’t have hurt to have more Italy, but the last section is full of foolish misunderstandings and nonsensical obstacles designed to keep them apart until the end of the book, and it’s all so unnecessary. I kept reading it, but I also kept saying “Oh for goodness’ sake.” Don’t bother.

Dancing to the Precipice: The Life of Lucie de la Tour du Pin and the French Revolution, Caroline Moorehead (2009)

Re-read. This is non-fiction about a woman’s life leading up to, through, and after the French Revolution, and it’s excellent. It was one of the first things I read on the French Revolution when I was starting to research it, and I wanted to read it again now with more context. It’s still great.

Moorehead is one of the best biographers out there, thorough, thoughtful, and a good writer. Lucie went through a lot and stayed resilient, and it’s just fascinating seeing a woman who was one of Marie Antoinette’s ladies-in-waiting milking cows in Albany and then going back and being at Napoleon’s court, and then surviving that and going on, while bearing children and losing children and bringing them up and coping with all of it. We have a lot of her letters and a memoir she wrote, so Moorehead had excellent primary sources for Lucie as well as the wider events, and focuses in on the personal within history in a way I wish more books could do.

Dissidence, Ken MacLeod (2016)

Volume 1 of the Corporation Wars trilogy. Terrorists from the near future wake up virtually in the far future to fight against newly sentient robots. Lots of intriguing worldbuilding, and excellent robots.

Insurgence, Ken MacLeod (2016)

Corporation Wars Volume 2. The first book didn’t have much volume completion so I went straight on. More virtual and robotic combat and political complexity, more characters and POVs. A really fun thing with someone who went undercover in the simulation and can manipulate reality in a Zen master kind of way.

Emergence, Ken MacLeod (2017)

Last volume of Corporation Wars. When everything is virtual, sometimes it’s hard to care. The resolution of these had me wondering why it was all worth it. The robots are great, but the wider issues hinted at in earlier books didn’t really go anywhere significant. It seems strange that the events of the near future, the conflict between Acceleration and Reaction, would have shaped the subsequent world to such an extent over such a long time, as if history really did end at that point, until this war.

Silver Birch, Blood Moon, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling (1999)

The last two stories in this book are by Robin McKinley and Patricia McKillip, and it really would have been worth the price of the whole anthology just for those two stories because they were so great. This is another volume in the series of reimagined fairy tales. The quality of the stories naturally varies, but the highs here are very high.

The Two Sides of the Shield, Charlotte M. Yonge (1885)

Sort of sequel to Scenes and Characters but as it’s about another generation, it doesn’t matter if you haven’t read the first one. This is the story of a girl who goes to live with her cousins, and of course at first she doesn’t like it and then later she does. Yonge is differently sentimental than the way we are sentimental now.

This is another book that made me think how different it would be as a historical novel—it would be both more and less satisfying, and the disability representation about be either absent or done differently, and it would be differently feminist. It is feminist, but not in an easily recognisable way. It’s very interesting to read things written in a period that take place in that period! Also, I love Yonge and reading her books is a treat. I’m not quite sure why I love her work so much, but I really do find it very easy to get caught up with her characters and care about her huge sprawling families and the tiny things that happen that assume such importance.

Meeting in Positano, Goliarda Sapienza (2015)

Translation of an Italian feminist novel with a lesbian main character who falls in love with both a woman and a town, to find love only sort of requited in both cases. It’s very good, beautifully written, but quite depressing. It’s neither as good nor as depressing as Elena Ferrante, and people who like Ferrante might like this too.

The Crooked Inheritance, Marge Piercy (2006)

Re-read. Poetry collection I hadn’t read since it first came out and enjoyed re-reading. As usual with Piercy’s poetry it is divided into love, family, politics, the natural world, spirituality, feminism, and all the sections are interesting and interconnected. The politics here are the invasion of Iraq and its aftermath, so not easy reading—her anger at that new betrayal really burns.

Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh, Leslie Brody (2020)

Louise Fitzhugh wrote Harriet the Spy (and some other children’s books, but especially that one). I knew nothing about her life before reading this. I did not like the way Brody made the chapter titles all about spying—and not the way Harriet spies, more like le Carré. I did not like her saying that lesbians identify with Harriet as if straight people did not also identify with her—I have identified with Harriet for a long, long time! I found Fitzhugh’s life itself interesting and surprising—her terrible relationship with her family, the fact that she was rich, the speed at which she went through girlfriends, her alcohol abuse—but I wasn’t very keen on the way this book was written. An interesting read, definitely.

On Friendship and On Old Age, Marcus Tullius Cicero (44 BC)

I read these in the Harvard Shelf of Books. I’d read pieces of them before in Latin, but never sat down and read them all through this way. They’re texts that have never been lost, that were carefully copied and considered all through the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, and that makes them true classics—and then I get whiplash because in some ways Cicero himself feels closer than the centuries through which the books have survived.

It was fun reading these so soon after reading the letters to Atticus where Cicero discusses who the speakers should be in the dialogues and who he should dedicate them to and so on. There is nothing particularly exciting or innovative here; how could there be in books that have been commonplaces on their subjects for two thousand years? But they were fun to read, and it’s interesting to think how attitudes to both these things have changed radically in the last century after changing much more slowly in all the time before that.

The Donut Trap, Julie Tieu (2021)

Romance novel about a woman of Chinese ancestry who is working in her parents’ donut shop in California as she finds both a boyfriend and a better job. Great characters and interesting background detail. Plausible romance. Great friend group. I also very much liked the difficult but well-described relationship with her immigrant parents. Fun, and well written.

The English Air, D.E. Stevenson (1940)

This book caused me more anxiety than anything else I read in February, including the out-and-out horror of Slade House. I am not often in suspense as to plot in genre novels, and this book is in the genre of sweet 1930s romance. It’s just… it was published in January 1940, and the hero is a half-German guy who comes to England in 1938 and realises that growing up a Nazi wasn’t all that good and falls in love with an English girl, and is torn between his two countries. I knew Stevenson would give it a happy ending, but… history! History I knew and she did not!

By halfway through I cared about the characters, and when he went back to Germany and joined the anti-Nazi underground I kept thinking that if this was an alternate history where he killed Hitler somebody would already have told me about it. My problem was that there were lots of things I knew that the author didn’t, because she was writing in 1939/40, and lots of plausibly happy endings she could have given the book that would have broken my heart… she thought Buchenwald was just an unpleasant kind of prison. Stevenson did manage to find a happy ending that worked for me, amazingly, but I worried an awful lot while I was reading this book.

If this were a historical WWII romance it would have been totally different, and I wouldn’t have been worried for a second. Franz wouldn’t have started as an enthusiastic Nazi who only saw what was wrong with it in England. The book would have contained Jews, or mentions of Jews. It would not have been enthusiastic and positive about the Maginot line, or about Chamberlain—I think this is the only book ever to do that. And I doubt it would have had the wonderful moment when the hero feels that he and Germany have no honour after Hitler violates the Munich Agreement. This is a strange book, and I recommend it, but it’s the opposite of comfort reading.

The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, Peter Frankopan (2016)

A book that starts in the Neolithic and goes up to 2016, focusing on the middle part of the world that lies between the extremes of Europe and China, and which has always been very important but has rarely been the focus of written history, especially in English. This is a history of the whole world, but with the focus in a different place. There was new information, but there was also a lot of information I already knew but differently presented. Smoothly written and interesting, and going right up to whirlwind-reaping that is still very much current.

The Rhine: Following Europe’s Greatest River From Amsterdam to the Alps, Ben Coates (2018)

Travel and history book written by British guy who lives in Rotterdam. He makes a trip along the whole length of the Rhine, recounting its history as well as his encounters. He walks, jogs, cycles, and takes boat rides. Sometimes he has his dog with him. Often when he has been talking about war in a particular region he talks about how peaceful it is now, how open the border is. He eats and drinks a lot as he goes. Not great literature, but definitely a fun read.

The Life of Elves, Muriel Barbery (2015)

Translated from French by Alison Anderson. I loved Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog but I hated this. This is an example of what Le Guin meant when she talked about watching someone falling off a tightrope while saying “I hope nobody will say I am a tightrope walker.” Fantasy written by a mainstream writer who reinvents the wheel all the time, and not in a good way, oh dear. Also kind of claustrophobic.

Age of Ash, Daniel Abraham (2022)

First in a new series; absorbing, excellent, masterful handling of fantastical elements. Many questions are opened but only some answered, but it still has good volume completion. Great characters, including female characters of many ages, great female friendship, great character arcs, excellent plausible and effective magic. This is not my favourite Abraham. I don’t know whether he’ll ever write anything I love as much as I love the Long Price books, which do so many things so well. But I thoroughly enjoyed this, I will buy the sequels as soon as they come out, and probably re-read this one first.

The Undateable, Sarah Title (2017)

Genre romance about a librarian whose face becomes a meme—”Disapproving Librarian Disapproves”—and how she finds love anyway. Funny and clever and full of empowered women of many different kinds. I was afraid it was going to sell out but it didn’t. I don’t usually like romance where the characters bicker all the way through, but this one utterly convinced me.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and fifteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her novel Lent was published by Tor in May 2019, and her most recent novel, Or What You Will, was released in July 2020. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.

Thank you for posting this! Added a couple books to my TBR and one for my kids as well.

I felt the same way about Slade House — it’s brilliant because it’s Mitchell but it’s horror so it’s not really my thing — but it’s still brilliant.

I have a D. E. Stevenson book thanks in part to Scott Thompson’s prompting at Furrowed Middlebrow (he’s like the biggest ever D. E. Stevenson fan, plus a fan of WWII homefront books, and I see he just reprinted The English Air — is that the edition you read?) … still haven’t read the one I have though.

And thanks as ever for the reminder that I need to read more Von Arnim! And I must get these new Marta Randall books.

While I’m sad to hear you spent February in pain, I remain impressed by the breadth of your reading. I must pick up the Randall novel – always wondered what happened after the first one.

Have you read Naomi Mitchison at all? Having read her Memoirs of a Spacewoman and been blown away by The Corn King and the Spring Queen, I recently read The Bull Calves (Scottish family after the ‘45) and Cleopatra’s People (Egypt after Cleopatra’s death, with a soupçon of Shakespeare for extra seasoning). In both books – in all of them – Mitchison says “Let me tell you a story” – and you’re hooked, even though the subjects of these novels could hardly be more different. I end up enjoying the ride, dying to know how the story ends and passionately concerned about the characters.

I read The Bird of Time recently myself, but after the first book (The Nick of Time). I daresay Bird makes more sense read after Nick but neither was actually good. (I read the second because like the first it was on my shelf and is short – not sure what fallacy that is.)

What? The suck fairy got to the Green Knowe books? Say it ain’t so! I was looking forward to re-reading those.

David Mitchell is a favorite. Only books I haven’t read by him are his first two. Sometimes I keep books from favorite writers until I just need some of their mojo. The Long Price Quartet is my absolute favorite Danial Abraham work, but I am glad Age of Ash is wonderful as well. Next on my list!

Ah, Silver Birch, Blood Moon is available as a Hoopla ebook through my library system! So I can read the last two stories in it this evening! It’s nice when there’s no delay in gratification.

I love Vikram Seth’s novel-in-verse The Golden Gate–sometimes it has been on my (fluctuating) Top Ten Favorite Novels list. I need to read some of his other poetry!

Sorry to hear it was a hard month for you, and thanks for keeping us up on your reading in spite of that. I hope spring brings a lessening of pain and an increase of mobility.

@Jo, sending you good wishes of less pain going forward. Thanks for sharing your reading; I enjoy this column very much.

Is it technically possible to write a better paragraph review of ‘Slade House’?

I don’t think so.

I too would like to express sympathy for your February. Mine was made much better by Age of Ash and I can’t wait for the next volume to come out. I just re-read the Long Price Quartet a couple of months ago and I really believe that Daniel Abraham ought to be getting the same kinds of accolades that N.K.Jemisin gets.